내가 처음 가진 궁금증이었다.

[조리개는 조리개의 수치가 클수록 열리는 원의 크기가 작아져서 빛이 조금 들어오고, 조리개의 수치가

작을수록 열리는 원의 크기가 커져서 빛이 많이 들어오게 된다]라고 되어있다.

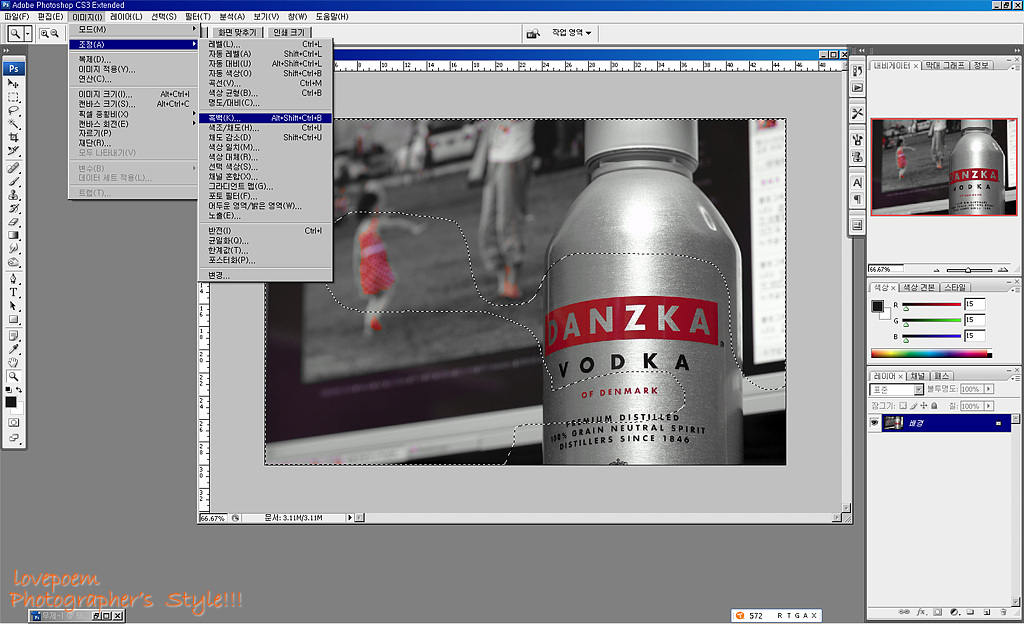

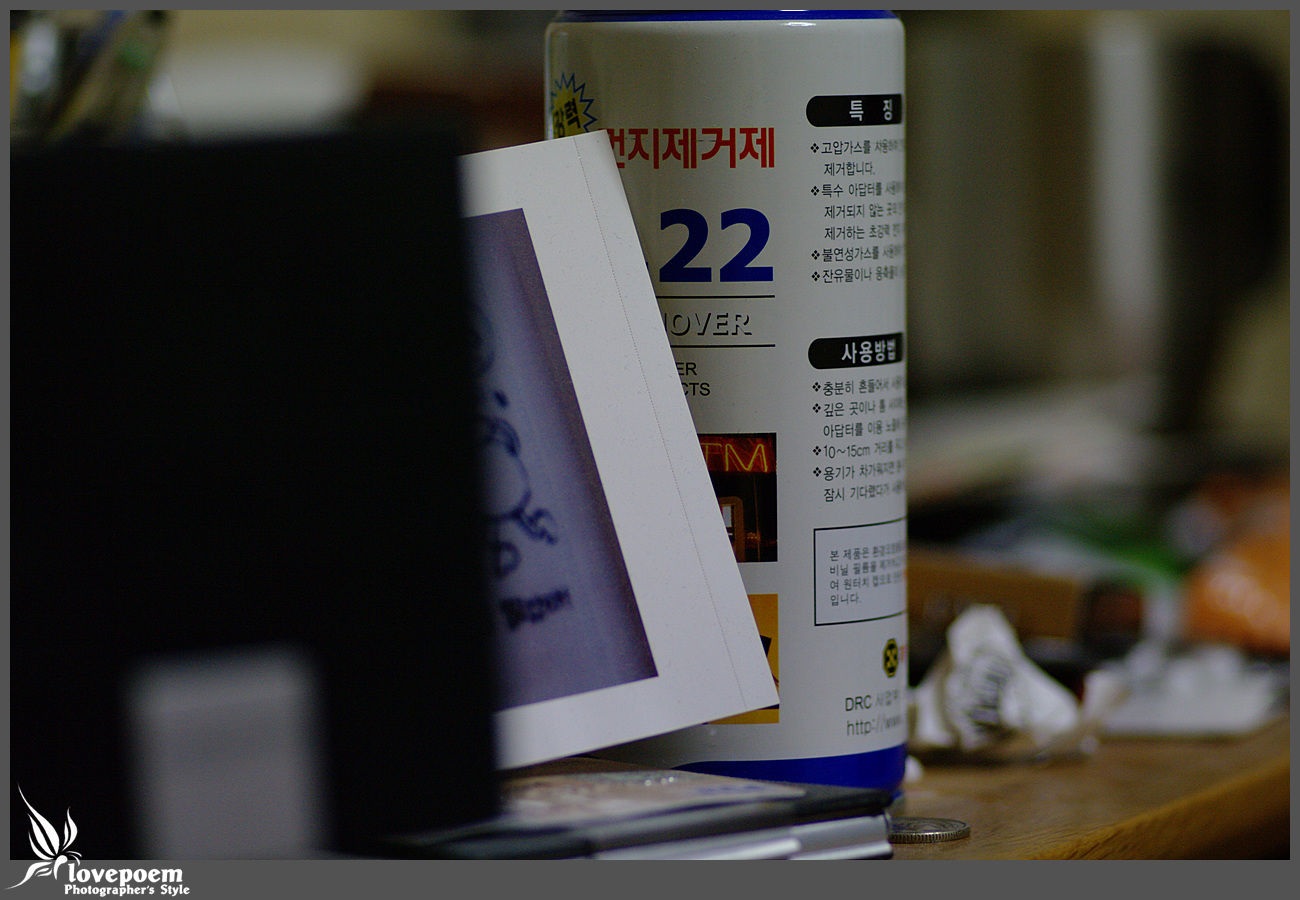

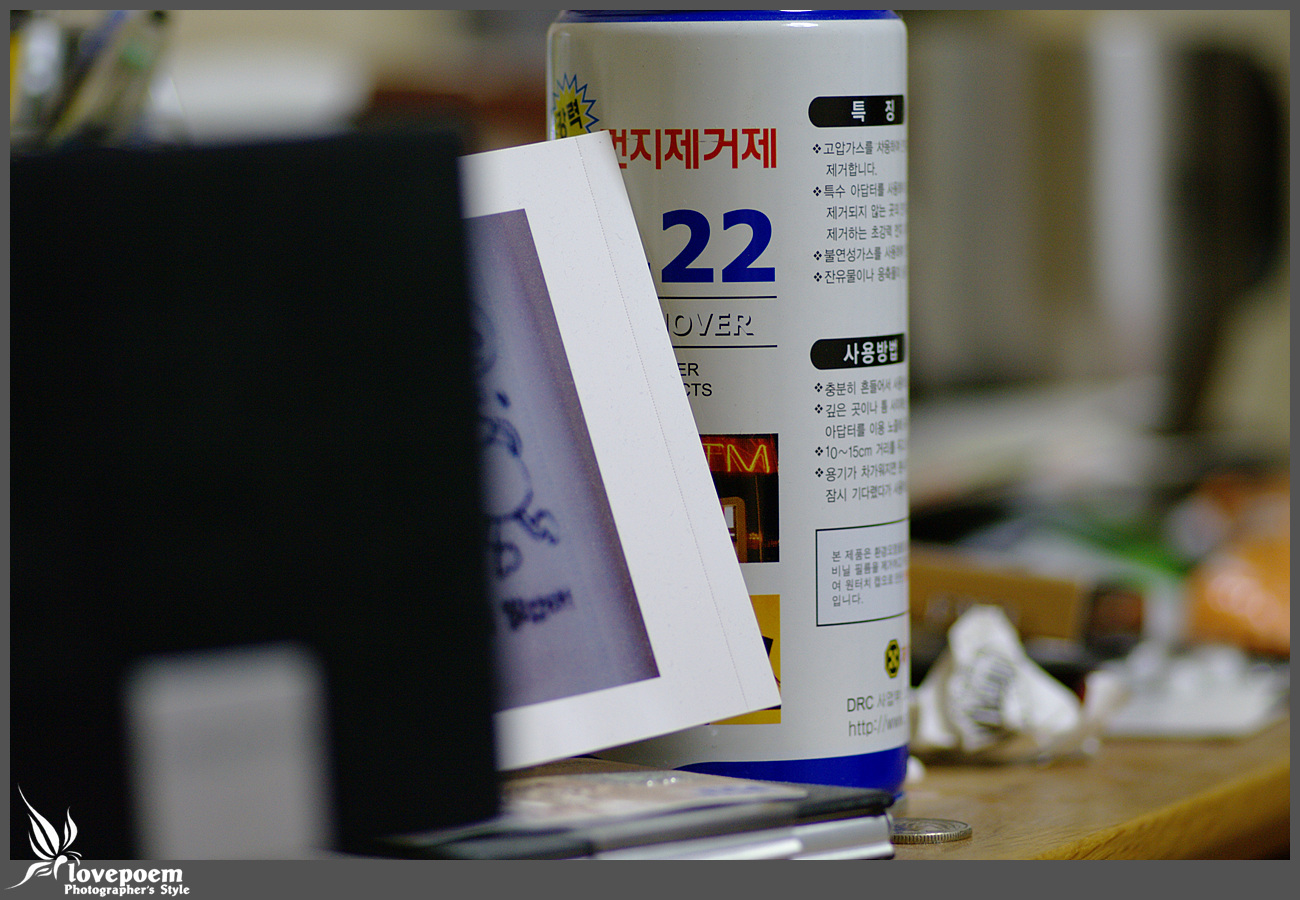

피닉스 50mm단렌즈로 보면 F22일때의 구멍크기는 아래와 같다.

이 크기는 사진 찍어놓은지 오래되어서 정확히는 모르지만 F5.6일것이다.

빛이 많이 들어오게 된다.

이 조리개는 피사체심도와도 관련이 있으므로 이해를 해두는게 좋다.

그럼 다시 왜 Aperture라는 영어단어를 쓰는 조리개의 수치는 F로 표시할까.

이유는 의외로 간단하다. 그저 수치단위의 표시일뿐이다. 영어단어의 앞글자를 표시한줄 알았었는데

그게 아니었다. 그냥 수치표시;;; (내용 수정합니다. 제일 아래에 설명이 있습니다 2019.6.16)

이유도 간단하고 궁금중도 쉽게 풀렸는데 또다시 떠오르는 궁금증 하나...

조리개는 왜 간단하게 표시안했을까.

사람의 눈으로 보는 밝기가 "F1"이라고 한다. 가만보면 카메라는 역시 사람의 눈이 기준이 되었었다.

셔터스피드 1/125도 눈깜박임속도를 기준으로 한거라는데.. 계산하기 쉽게 1/120대신 1/125로 했다는게

더 설득력 있음..^^; 각설하고..

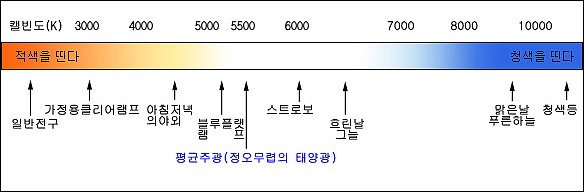

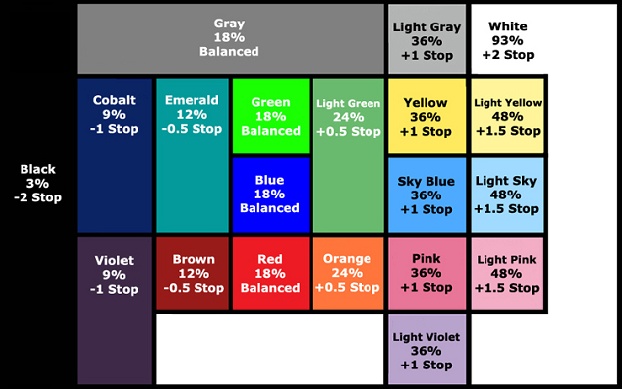

사람의 눈으로 보는 밝기를 기준으로 F1 을 기준으로 1/2밝기를 계산하면 F1.4가 나온다.

그다음 F1.4의 1/2밝기는 F2, F2의 1/2밝기는 F2.8이다.

한단계씩 두배의 밝기차이가 있다.

눈치빠른분이라면 보일만한 간단한 규칙. 숫자상으로 두배이면 1/4배의 밝기차이가 난다.

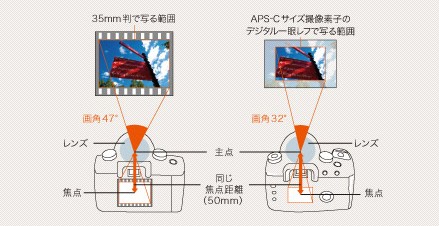

실제 조리개의 계산법은 "F값 = 렌즈의 초점거리 / 조리개의 직경"이다.

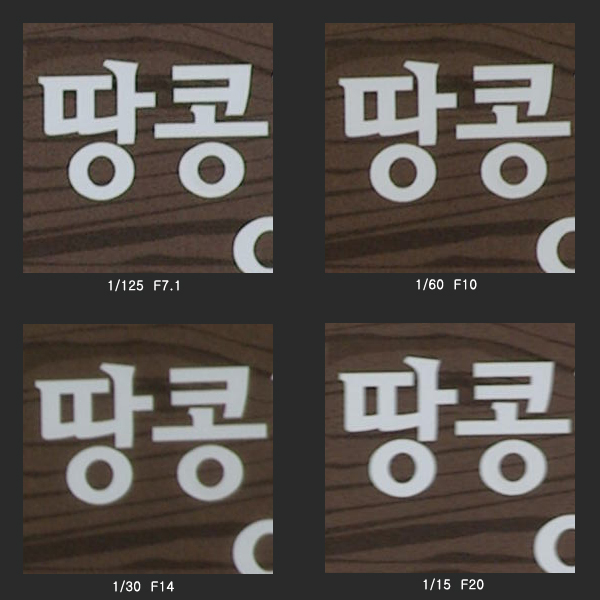

조리개를 F4까지 더 열었을때 셔속은 1/250초까지 맞춰도 노출은 같게 된다.

위에서 거론되었던 피사체심도를 표현함에 있어 조리개수치는 상당히 중요하다.

를 말한다.

2019.6.16

# 추가 : F값(F/n)을 최초로 기준을 정한 내용을 찾았기에 추가설명합니다. 아래 링크의 "History"섹션에 나와있습니다.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F-number

상대적인 조리개의 기원을 보면 "apertal ratio" 조리개 비율을 정의했구요.

1880년대 영국의 왕립사진학회에서 표준으로 채택되었습니다. "f-number system" "f/x system"으로 불렸습니다.

많은 사람들이 이 "F"를 초점거리(Focal)에서 온걸로 얘기하는데 그 출처가 궁금합니다. 사진 역사에서 최초로 F값을 정의한 사람 혹은 단체가 그렇게 정의내렸다는 기록은 아직 발견 못했습니다.(제 기준입니다)

초점거리에 의해서 F값이 달라지기도 하지만 조리개 직경에 따라서도 F값은 달라집니다. 초점거리만이 기준이 아닙니다.

f값은 초점거리(focal) / 직경(diameter) = N으로 나타내는데 (쉽게 N=f/d) 여기서 N은 NA입니다. 물론 사진학에서 NA를 사용치 않고 광학분야에서 사용됩니다만 의미는 Numerical Aperture(조리개수치)로 같은것으로 압니다.

Numerical aperture(조리개수치)는 다른말로 Aperture ratio(조리개 비율) Fractional diameter(직경의 분수값)으로도 표현될 수 있습니다..

그외에도 "ratio number" "aperture ratio number" "ratio aperture"라고도 불리웠었던것을 아래의 자료를 통해서 알 수 있습니다.

결론 이 f값은 초점거리(focal) 와 직경(diameter)의 분수값(나눈값) - Fraction - 을 나타냅니다.

f-number N=f/d, 초점(focal)과 분수(fraction)중에서 더 어울리는 단어가 무엇일까요.

Origins of relative aperture

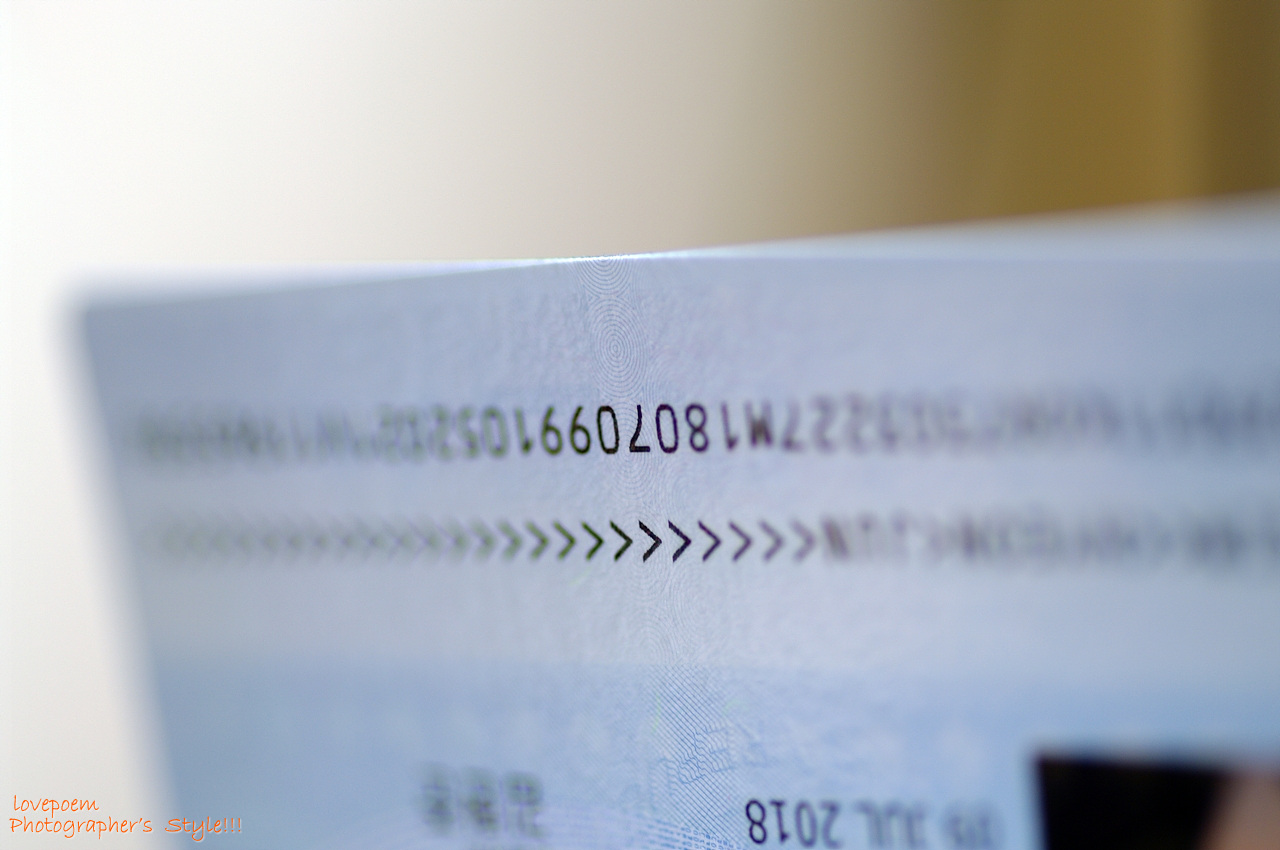

In 1867, Sutton and Dawson defined "apertal ratio" as essentially the reciprocal of the modern f-number. In the following quote, an "apertal ratio" of "1⁄24" is calculated as the ratio of 6 inches (150 mm) to 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm), corresponding to an f/24 f-stop:

In every lens there is, corresponding to a given apertal ratio (that is, the ratio of the diameter of the stop to the focal length), a certain distance of a near object from it, between which and infinity all objects are in equally good focus. For instance, in a single view lens of 6 inch focus, with a 1⁄4 in. stop (apertal ratio one-twenty-fourth), all objects situated at distances lying between 20 feet from the lens and an infinite distance from it (a fixed star, for instance) are in equally good focus. Twenty feet is therefore called the 'focal range' of the lens when this stop is used. The focal range is consequently the distance of the nearest object, which will be in good focus when the ground glass is adjusted for an extremely distant object. In the same lens, the focal range will depend upon the size of the diaphragm used, while in different lenses having the same apertal ratio the focal ranges will be greater as the focal length of the lens is increased. The terms 'apertal ratio' and 'focal range' have not come into general use, but it is very desirable that they should, in order to prevent ambiguity and circumlocution when treating of the properties of photographic lenses.[17]

In 1874, John Henry Dallmeyer called the ratio {\displaystyle 1/N} 1/N the "intensity ratio" of a lens:

The rapidity of a lens depends upon the relation or ratio of the aperture to the equivalent focus. To ascertain this, divide the equivalent focus by the diameter of the actual working aperture of the lens in question; and note down the quotient as the denominator with 1, or unity, for the numerator. Thus to find the ratio of a lens of 2 inches diameter and 6 inches focus, divide the focus by the aperture, or 6 divided by 2 equals 3; i.e., 1⁄3 is the intensity ratio.[18]

Although he did not yet have access to Ernst Abbe's theory of stops and pupils,[19] which was made widely available by Siegfried Czapski in 1893,[20] Dallmeyer knew that his working aperture was not the same as the physical diameter of the aperture stop:

It must be observed, however, that in order to find the real intensity ratio, the diameter of the actual working aperture must be ascertained. This is easily accomplished in the case of single lenses, or for double combination lenses used with the full opening, these merely requiring the application of a pair of compasses or rule; but when double or triple-combination lenses are used, with stops inserted between the combinations, it is somewhat more troublesome; for it is obvious that in this case the diameter of the stop employed is not the measure of the actual pencil of light transmitted by the front combination. To ascertain this, focus for a distant object, remove the focusing screen and replace it by the collodion slide, having previously inserted a piece of cardboard in place of the prepared plate. Make a small round hole in the centre of the cardboard with a piercer, and now remove to a darkened room; apply a candle close to the hole, and observe the illuminated patch visible upon the front combination; the diameter of this circle, carefully measured, is the actual working aperture of the lens in question for the particular stop employed.[18]

This point is further emphasized by Czapski in 1893.[20] According to an English review of his book, in 1894, "The necessity of clearly distinguishing between effective aperture and diameter of physical stop is strongly insisted upon."[21]

J. H. Dallmeyer's son, Thomas Rudolphus Dallmeyer, inventor of the telephoto lens, followed the intensity ratio terminology in 1899.

Aperture numbering systems

At the same time, there were a number of aperture numbering systems designed with the goal of making exposure times vary in direct or inverse proportion with the aperture, rather than with the square of the f-number or inverse square of the apertal ratio or intensity ratio. But these systems all involved some arbitrary constant, as opposed to the simple ratio of focal length and diameter.

For example, the Uniform System (U.S.) of apertures was adopted as a standard by the Photographic Society of Great Britain in the 1880s. Bothamley in 1891 said "The stops of all the best makers are now arranged according to this system."[23] U.S. 16 is the same aperture as f/16, but apertures that are larger or smaller by a full stop use doubling or halving of the U.S. number, for example f/11 is U.S. 8 and f/8 is U.S. 4. The exposure time required is directly proportional to the U.S. number. Eastman Kodak used U.S. stops on many of their cameras at least in the 1920s.

By 1895, Hodges contradicts Bothamley, saying that the f-number system has taken over: "This is called the f/x system, and the diaphragms of all modern lenses of good construction are so marked."[24]

Here is the situation as seen in 1899:

Piper in 1901[25] discusses five different systems of aperture marking: the old and new Zeiss systems based on actual intensity (proportional to reciprocal square of the f-number); and the U.S., C.I., and Dallmeyer systems based on exposure (proportional to square of the f-number). He calls the f-number the "ratio number," "aperture ratio number," and "ratio aperture." He calls expressions like f/8 the "fractional diameter" of the aperture, even though it is literally equal to the "absolute diameter" which he distinguishes as a different term. He also sometimes uses expressions like "an aperture of f 8" without the division indicated by the slash.

Beck and Andrews in 1902 talk about the Royal Photographic Society standard of f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11.3, etc.[26] The R.P.S. had changed their name and moved off of the U.S. system some time between 1895 and 1902.